The Missing piece of the jigsaw

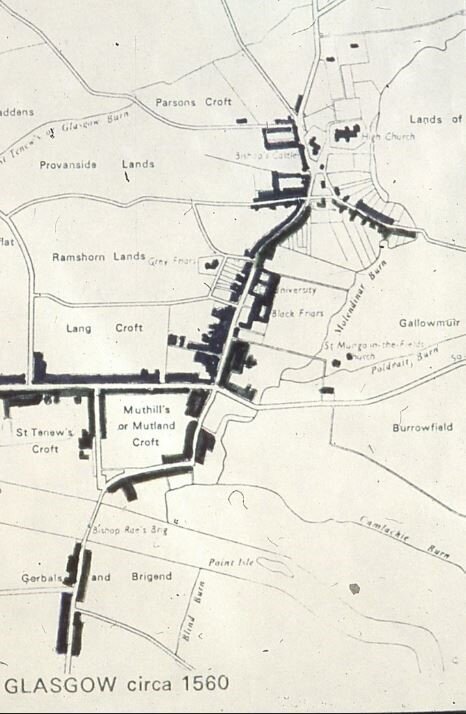

The jigsaw of Glasgow started with a convenient ford to cross the River Clyde. A small community developed here and wound its way up the hill to the north, on what is now High Street, to the Cathedral. As global trade developed, the settlement grew dramatically to the west over what is now The Merchant City, and by the mid-19th century The City of Glasgow had become “the second city of the empire”, manufacturing and exporting goods all over the world, and the grid-iron street pattern started to march across the drumlins left by the glaciers scraping though the Clyde valley.

Glasgow was surrounded geologically by plentiful supplies of natural building stone, initially in a warm buff colour, but later red sandstone quarries joined the supply chain. This accident of nature provides the historic streetscape of Glasgow with a grand scale and lively natural surface backdrop to life in the city, not to mention the art carved deep into the stones from simple jointing to full sculpture.

The jigsaw of Glasgow is therefore strong, beautiful, and inspirational.

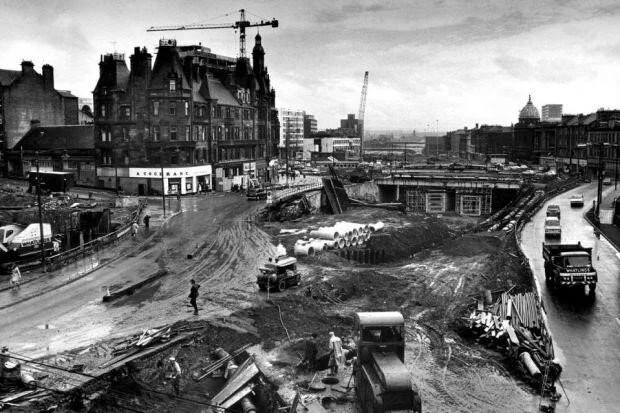

The love of this pattern is strengthened in the people of Glasgow by the controversial disregard of the grid through the 1960s and 70s, as the post-industrial city desperately tried to reinvent itself. Great motorways were carved through the centre of the city and whilst certainly making Glasgow extremely accessible by motor vehicle, these roads crashed through the historical fabric and tore open the grid. At the same time the dire slum conditions in places like The Gorbals were dealt with in a crude policy of demolition and clearance, moving whole populations to the new periphery estates. Add to this, modern ways of living and working, which left once proud historic buildings vacant without a viable future, and the jigsaw was looking worse for wear, with tears and gaps.

In recognition that the modern interventions had catapulted the baby out with the bath water, the destruction was curtailed by the end of the 1970s and recognising that the existing buildings had huge merit a new move to refurbish and restore found its place. In particular, the cleaning of the soot blackened stone uncovered the original attractiveness and warmth. A new generation of architects started to design repairs to the grid, and the development pressure on much loved areas of the city where the historic fabric was still dominant, brought secondary land into viability for new buildings, particularly housing.

Sensitivity was to the fore, and the new designs referenced the historic fabric in both materials and style. There was a recognition that the history had value, both in terms of cultural memory and in its own beauty and power.

Our response

We have contributed our pieces to the Glasgow jigsaw over the years. In a major step forward for the City, the Crown Street development in the Gorbals re-created a Glasgow grid and populate it with modern tenement housing, together with parks and shops. Holmes Miller designed three phases within this development, which has set a benchmark for repairs to the grid. These developments were four storey tenement flats, the traditional Glasgow model, with parking on the street and common landscaped parks behind for recreation, as opposed to the traditional drying green.

On the corner of Minerva Street where the practice developed its office from an old factory unit 25 years ago, a vacant office building was demolished and the site purchased for residential development. The site sits across from a beautiful Victorian terrace of flats, including the A Listed St Vincent Crescent, and on the border between the historic residential Finnieston area and the industrial land towards the river. We designed a block of 55 flats over two levels of parking, with front façade following the curve of the street and finished with natural buff stone as a match to the listed neighbours opposite. Care was taken to match the stone to the height of the existing gutter across the street, and two storeys of well set back zinc cladding houses the penthouses across from the old existing pitched roofs.

Our niche development at the Old Primary School in Lenzie takes a beautiful Victorian building with its attractive sandstone elevations and beautiful central atrium and, together with a contemporary and complimentary extension, carves out a development of 20 flats and maisonettes, all suitable for the downsizer market which Lenzie badly needs. This development shows the wider community value of these interventions in that it brings life into a local infrastructure which already exists and so provides trade for local shops and cafes.

We have also tackled one of the more ‘aggressive’ modernist buildings at Herschell Street in Anniesland to the west of the city. This old government office was constructed from a pebble finished precast concrete façade, which is also the structure. By putting a facing brick ‘overcoat’ around this frame and a new penthouse ‘lid’ we have regenerated the building with 48 flats in a highly sustainable manner – we have recycled the building!

And of course there’s our development at Park Quadrant – the ultimate “missing piece of the jigsaw” – where a site intended for development in the original Victorian masterplan for Park Circus, but not built for over a hundred years, is now appearing out of the scaffold with a contemporary grandeur to compliment the original Park development – more to follow…